‘The more things change, the more they stay the same.’ (A. Karr)

‘The more things change, the more they stay the same.’ (A. Karr)

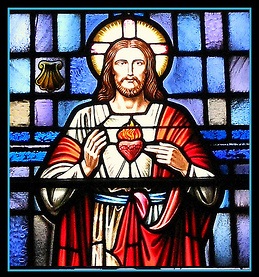

During my childhood, a picture of the Sacred Heart hung on the wall of our living room – kindly watching over us, protecting us, loving us. That picture was a sacramental in my life, a tangible reminder of God’s unconditional love. Often I would pray by talking out loud to the kind and good God represented by that picture. Intuitively, I understood that the heart, so graphically portrayed, was symbolically beating with love for me. The eyes which seemed to follow me as I moved around the room were kindly watching over me with love. I found it hard to have a relationship with God the Father in Heaven, or the Holy Spirit, who was like the wind which blows wherever it wills (John 3:18), but Jesus Christ, who loved me enough to die for me, was alive and real.

As I grew older and felt pain when people said unkind things, or I had to deal with failure and worry in life, I would pray, “Sacred Heart of Jesus, I place all my trust in Thee,” and peace would flood my being. God was in charge. Whenever I turned away from God, Jesus would call me back to His Sacred Heart and I would feel welcomed, forgiven and loved back to wholeness. I knew, even from childhood, that the Sacred Heart is another name for Jesus; that devotion to the Sacred Heart is a devotion to Jesus. The heart of Jesus Christ represents His divine love and compassion for us all, or as Pope Pius XII puts it (in his 1956 encyclical Haurietis aquas), the Sacred Heart is venerated as “a symbolic image of His love and a witness of our redemption.” The pope wanted the whole Church to recognize the Sacred Heart as an important dimension of Christian spirituality; a view taken by the Jesuits from the early days.

However, even though the Jesuits have always been strongly associated with the devotion, in 1981 Pedro Arrupe S.J., then the superior general of the Jesuits, had to remind the Society of Jesus: “I have always been convinced that what we call ‘Devotion to the Sacred Heart’ is a symbolic expression of the very basis of the Ignatian spirit.” Yet Fr. Arrupe acknowledged, “In recent years the very expression ‘Sacred Heart’ has constantly aroused, from some quarters, emotional, almost allergic reactions.”

Fr. James Martin has observed “that those ‘allergic reactions’ mean that we are missing a powerful and vivid symbol of the love of Jesus. For the Sacred Heart is nothing less than an image of the way that Jesus loves us: fully, lavishly, radically, completely, sacrificially. The Sacred Heart invites us to mediate on some of the most important questions in the spiritual life. In what ways did Jesus love His disciples and friends? How did He love strangers and outcasts? How was He able to love His enemies? How did He show His life for humanity? What would it mean to love like Jesus did? What would it mean for me to have a heart like His? How can my heart become more ‘sacred’? For in the end, the Sacred Heart is about understanding Jesus’ love for us and inviting us to love others as Jesus did” (America, June 15 2012).

However, the world has become less sympathetic towards taking a symbolic view of a graphic representation of a heart bleeding and looking so ‘gruesome’. In our increasingly literal world, the image of the Sacred Heart now repels many. Fr. Martin suggested that “Perhaps newer images are needed to revive this devotion.” Perhaps we need new ways to represent the truth that the Sacred Heart signifies.

Fortuitously, a Polish nun, St. Mary Faustina (1905-1938), reported a number of apparitions, visions and conversations with Jesus which were published as the book Diary: Divine Mercy in My Soul. Subsequently the Polish Pope St. John Paul II encouraged the spread of the Divine Mercy Devotion and the Sunday following Easter Sunday was designated as Divine Mercy Sunday. The primary focus of this devotion is the merciful love of God and the desire to let that love and mercy flow through one’s own heart towards those in need of it. Interestingly, ‘Jesus, I trust in you’ is the signature on the Divine Mercy image, echoing the Sacred Heart prayer.

And so I ask: might this be the Holy Spirit at work, rendering an image more acceptable to modern sensibilities, which continues to offer the faithful a representation of the love and compassion of Jesus? Perhaps the Divine Mercy Devotion is the Sacred Heart Devotion updated for the 21st century?

I am reminded of William Shakespeare’s question from Romeo and Juliet,

“What is in a name? That which we call a rose

By any other name would smell as sweet” (Act II, scene ii).